Removing React is just weakness leaving your codebase

by Simon MacDonald

@macdonst@mastodon.online

on

Apologies to Chesty Puller for appropriating his quote, “Pain is weakness leaving the body.”

It’s 2024, and you are about to start a new project. Do you reach for React, a framework you know and love or do you look at one of the other hot new frameworks like Astro, Enhance, 11ty, SvelteKit or gasp, plain vanilla Web Components?

In this post, I will enumerate why I no longer use React and haven’t for the past two years after 7 years of thrashing about with the library.

Quick note: I started writing this post before taking off for the holidays. Well, there must have been something in the zeitgeist, as we’ve seen a spate of articles where developers are voicing their displeasure with React.

- Increasingly miffed about the state of React releases by Tom MacWright

- Kind of annoyed at React by Cassidy Williams

- React, where are you going? By Matteo Frana

- The Decline of React by Chris Ferdinandi

- Concatenating text by Johan Halse

It’s not that React has been immune to criticism, as Zach Leatherman has detailed in his post A Historical Reference of React Criticism, but it sure seems like we’ve reached a tipping point.

The Shiny Object Syndrome

React has used the shiny object syndrome to its advantage.

Shiny object syndrome is the situation where people focus undue attention on an idea that is new and trendy, yet drop it in its entirety as soon as something new can take its place.

So, how is React like the shiny object syndrome? Obviously, there was a lot of hype around React when it was originally released by Meta nee Facebook, which had developers flocking to the library.

Whether on purpose or not, React took advantage of this situation by continuously delivering or promising to deliver changes to the library, with a brand new API being released every 12 to 18 months. Those new APIs and the breaking changes they introduce are the new shiny objects you can’t help but chase. You spend multiple cycles learning the new API and upgrading your application. It sure feels like you are doing something, but in reality, you are only treading water.

Just in the time that I had been coding React applications, the library went through some major changes.

- 2013: JSX

- 2014: React createElement API

- 2015: Class Components

- 2018: Functional Components

- 2018: Hooks

- 2023: React Server Components

By my reckoning, if you’ve maintained a React codebase for the past decade, you’ve re-written your application at least three times and possibly four.

Let’s take React out of the equation and imagine you had to justify to your boss that you needed to completely re-write your application every 2.5 years. You probably got approved to do the first rewrite, you might have got approval for the second rewrite but there is no way in hell you got approval for the third and fourth rewrites.

By choosing React, we’ve signed up for a lot of unplanned work. Think of the value we could have produced for our users and company if we weren’t subject to the whims of whatever the cool kids were doing over in React.

Stop signing up for breaking changes!

The Rule of Least Power

When building web applications, we should remember the rule of least power.

When designing computer systems, one is often faced with a choice between using a more or less powerful language for publishing information, for expressing constraints, or for solving some problem. This finding explores tradeoffs relating the choice of language to reusability of information. The “Rule of Least Power” suggests choosing the least powerful language suitable for a given purpose.

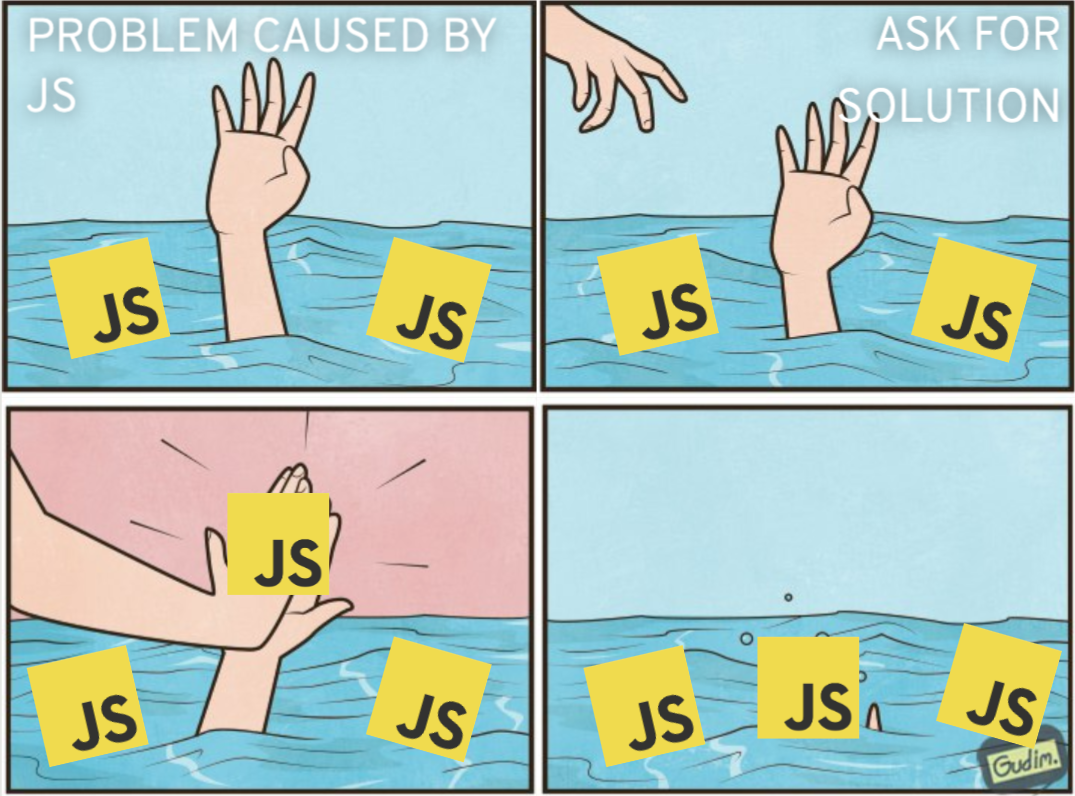

When building on the web, we could take this to mean that we should start with a base of HTML for our content, add CSS for presentation where necessary, and finally sprinkle in JavaScript to add interactivity and other capabilities that HTML and CSS cannot handle. React flips this on its head by starting with JavaScript to generate the HTML content, adding JavaScript to apply the CSS presentation too, and finally adding yet more JavaScript to apply the interactivity.

This contravenes the rule of least power.

Presentation

Here’s a simple React heading component.

function MyHeading({ children }) {

return (

<h2>{children}</h2>

);

}It looks like you are writing HTML, but you are not. You’re writing JSX (JavaScript syntax extension). Fundamentally, JSX just provides syntactic sugar for the React.createElement(component, props, ...children) function. So the JSX <MyHeading>My Heading</MyHeading> code compiles to:

React.createElement(

MyHeading,

{},

'My Heading'

)While you may think you are writing HTML, you are actually adding a lot of unnecessary (and possibly unexpected) JavaScript to your application.

Styling

CSS in JS libraries are very popular in React applications as they allow you to avoid learning CSS take a component-based approach to styling. The original CSS in JS library was developed by Christopher Chedeau, a front-end engineer who worked on the React team at Meta.

Let’s use JSS for our example:

import React from 'react'

import {createUseStyles} from 'react-jss'

const useStyles = createUseStyles({

myButton: {

color: 'green',

margin: {

top: 5,

right: 0,

bottom: 0,

left: '1rem'

},

'& span': {

fontWeight: 'bold'

}

},

myLabel: {

fontStyle: 'italic'

}

})

const Button = ({children}) => {

const classes = useStyles()

return (

<button className={classes.myButton}>

<span className={classes.myLabel}>{children}</span>

</button>

)

}This is great because we’ve been able to co-locate our styles with our components, but it comes at a cost: performance.

A quick reminder of how browsers work: first, it downloads your HTML. Then, it downloads any CSS from the head tag and applies it to the DOM. Finally, it downloads, parses and executes your JavaScript code. Because you have added your CSS declarations in all of your components, your JavaScript bundle is larger than it would be for a non-CSS in JS solution. This will increase the time it takes to parse your code just because of the larger bundle size, as well as the execution time due to the additional function calls to serialize the CSS.

We are drowning in JavaScript.

Use less of it.

This is not new advice.

Who’s running React these days?

No really. Who is running React? React’s last official release (as of this writing) is 18.2.0, released on June 14th, 2022. That was 19 months ago. To me, that signals that Facebook, er Meta, is no longer interested in pushing the library forward and instead, IMHO has ceded the leadership of React to the frameworks.

Is this a good thing? I’m not too sure. One problem with this arrangement is that Vercel is a venture-capitalist-backed startup, and they need to show a return on investment to their investors. As we’ve seen in the industry in the past year, VC funding is drying up. God forbid something happens to Vercel, but what happens to Next.js — and, to a greater extent, React — if Vercel disappears?

Additionally, there are worries about Vercel’s current stewardship of React. For instance, Next.js uses Canary versions of React because those are “considered stable for libraries.” That seems quite odd to me. As well, Next.js overrides the global implementation of node fetch, which leads to problems — a decision that the Next.js team seems to be rethinking.

I’m not the only one worried about this, as the Remix team has forked React into their organization. No commits yet, but it makes you wonder.

Where do we go from here?

This post may feel pretty negative to you, and from my point of view, it was born of the frustration I’ve had dealing with React applications as a developer and an end user. Don’t even get me started on the GitHub rewrite, which doesn’t seem to be going too well.

Just so we are clear, you weren’t wrong to choose React for previous projects. It is/was a hugely popular library. Companies were hiring React developers, and you needed a job. No one here is saying you were wrong to use React to further your career.

However, here is my unsolicited advice:

- If you are starting a new project today, evaluate the other options like Enhance, Astro, 11ty, SvelteKit, and vanilla Web Components.

- If you are currently maintaining an existing React application, investigate how you can add web components to your project. Web components are library agnostic, so you can begin to future-proof your application. (Angular, React, Vue)

- Inquire how you can use HTML and CSS to replace some of the things you do in JavaScript currently.

Conclusion

It may seem hyperbolic to say that React is a liability lurking in your codebase, but is it? You are staring down an eventual React 19.0 release, which will introduce a number of breaking changes, forcing you to rewrite your application yet again.

Why?

Is it React’s vaunted developer experience benefits? Or is it the better user experience? Nope and nope!

My suggestion is to start investigating how you can remove this weakness from your codebase. Look at ways to de-risk what will be yet another rewrite.

And then level up even further by learning web fundamentals.

The web is backward and forward compatible. Anything you learn about HTML, CSS and browser API’s will serve you well for the next 25 years, which is not something you can say about the current fashion in JavaScript libraries. By ejecting from the thrash of React and other heavy-handed frameworks and doubling down on web fundamentals, you’ll be future-proofing both your career and your codebases.

Web Mentions

-

@lukeharby 1/29/2024

-

Unknown 1/31/2024

Source: "Switching costs" -

@hbuchel 1/27/2024

-

@hbuchel 1/27/2024

-

@hbuchel 1/27/2024

-

@developit 1/29/2024

-

@hbuchel 1/27/2024

-

@hbuchel 1/27/2024

-

@macdonst 1/29/2024

-

@hbuchel 1/27/2024

-

@vesto 1/27/2024

-

@danielinoa 1/29/2024

-

@hbuchel 1/27/2024

-

@hbuchel 1/29/2024

-

Heather Buchel 1/27/2024

-

@vesto 1/27/2024